History of Québec City

Founded in 1608 by the French explorer Samuel de Champlain, Québec City is unlike any other city in North America with its dramatic cliff-top location overlooking the St. Lawrence River, its fortification walls, narrow winding streets and wealth of historic buildings spanning four centuries. Besieged five times in its history, Québec City was finally conquered by the British in 1759. Capital of New France, then capital of British North America, it is, today, the heart of French culture on this continent.

What are the origins of this unique and fascinating city? How has such an unusual place managed to survive and flourish over so many centuries? To begin to appreciate the history of French Canadians and the crucial role that Québec City has played in the destiny of North America, we need to think back to a time when the present-day borders of Canada and the United States did not yet exist. Here is an overview of the rich history of Québec City.

Summary

- The “Discovery” of Canada

- Origin of the Name Canada

- A Strategic Location

- The Founding of Québec City

- Capital of the Colony of New France

- French Historical Influence in Québec

- Struggle for a Continent

- A World at War

- The Battle of the Plains of Abraham

- The Treaty of Paris in 1763

- Westward Expansion Leads to More Conflict

- Québec Act of 1774 and the American Revolution

- One of the Greatest Ports on the Continent

- Economic Decline and Hard Times

- A City Preserved: Tradition and Modernity

- The Fortifications Are Saved From Destruction

- A UNESCO World Heritage Site

- French and British Influences in Québec City

- Québec Main Historic Sites Are Just a Few Minutes’ Walk Away

The “Discovery” of Canada

Historical tradition has often attributed the discovery of Canada to French explorer Jacques Cartier, who first sailed into the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 1534. The following year, he proceeded upriver to the Iroquoian village of Stadacona, which stood on the site where Québec City is located today. Of course, while Cartier’s voyages were a “discovery” from his point of view, he encountered Indigenous people who had already been living in the land now called Canada for many thousands of years.

In any case, Jacques Cartier, whose voyages had been commissioned by the King of France, was not the first European to come here. Other, less official visitors had certainly preceded him. Indeed, when Cartier first entered the Gulf, he sailed past vessels of Basque fishermen who had already been plying those waters for decades. Moreover, archaeological evidence has proven that Vikings from Europe had come to the country we now call Canada much earlier still, when they established a temporary settlement in Newfoundland, approximately 1000 years ago.

Origin of the Name Canada

Even so, Jacques Cartier was the first European to draw accurate maps of the areas that he explored, as he travelled up the St. Lawrence River, inland, as far as the present sites of Québec City and Montreal. He was also the first European to call the regions that he encountered by the name Canada, a word that he took from the Huron-Iroquois “Kanata,” which means village or settlement.

At first, the name Canada was only used to designate the area around the Iroquoian village of Stadacona. With time, however, it would be used to define ever-larger regions, so that, today, Canada is the name of the second-largest country in the world.

A Strategic Location

The name Québec has its origin with an Algonquin indigenous word, meaning “where the river narrows.” From the cliffs of Québec, it was possible for cannons to fire across the river and, hopefully, prevent enemy ships from penetrating further west. The great cliff of Québec, dominating the St. Lawrence from a height of more than 100 meters, makes the site a natural fortress. Over the centuries, the French, the British and then the Americans all fought to control this very strategic location.

The Founding of Québec City

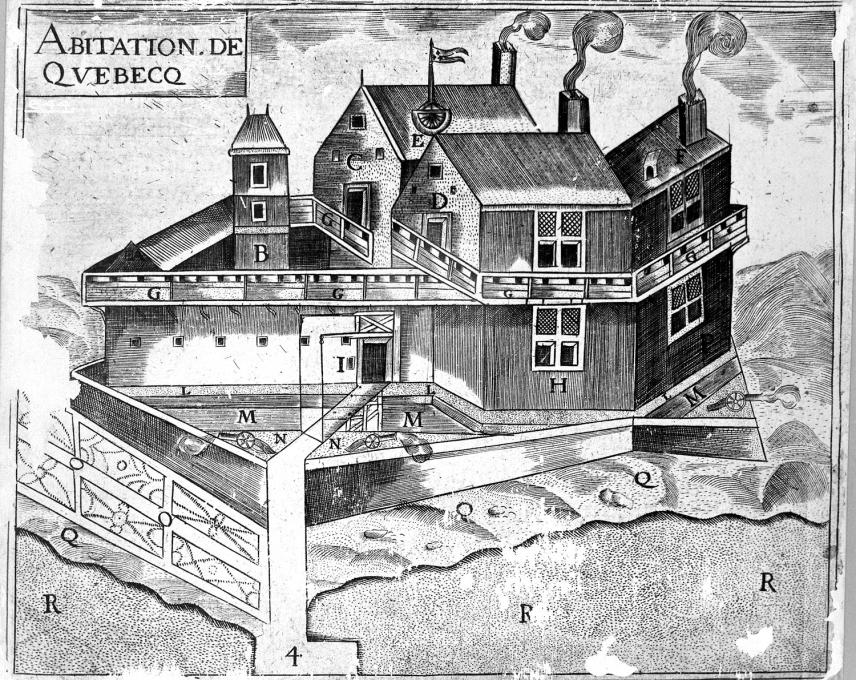

BAnQ. Habitation de Champlain (abitation de Québec) (P560.P644)

BAnQ. Habitation de Champlain (abitation de Québec) (P560.P644)

After Jacques Cartier, the French did not return for many years. They had problems in Europe, with religious wars and other difficulties. Who founded Québec? It wasn’t until 1608 that French explorer Samuel de Champlain established a trading post on the site of Québec. At first, the sparsely populated location was controlled by private fur trading companies based in France. But, by 1645, when locally based merchants took over, the trading post had evolved into a small settlement. In 1663, Louis XIV, “the Sun King,” chose the strategic site of Québec to become the capital of New France, a royal province under his direct authority.

Capital of the Colony of New France

A view of Quebec from the South-East, engraving, in Atlantic Neptune, 1781. Joseph Frederick Wallet DesBarres, BAnQ Collection Literary and Historical Society of Quebec

A view of Quebec from the South-East, engraving, in Atlantic Neptune, 1781. Joseph Frederick Wallet DesBarres, BAnQ Collection Literary and Historical Society of Quebec

This fortified city and inland seaport, hundreds of kilometres from the Atlantic, would serve as a control point between the Atlantic World and the vast network of navigable rivers and lakes that would become the lifeblood of the French empire in North America. French expansion, along the St. Lawrence, to the Ottawa River and the Great Lakes, then down the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico, has been compared to the growth of the branches of a tree.

Forts and trading posts were established along the main rivers and then their principal tributaries, providing access ever deeper into the hinterland. Many North American cities considered as English-speaking began as French forts and trading posts: Le Fort Toronto is now Toronto, Ontario; Le Fort Frontenac is now Kingston, Ontario; Détroit is now Detroit, Michigan; and La Nouvelle Orléans is now New Orleans, Louisiana.

French Historical Influence in Québec

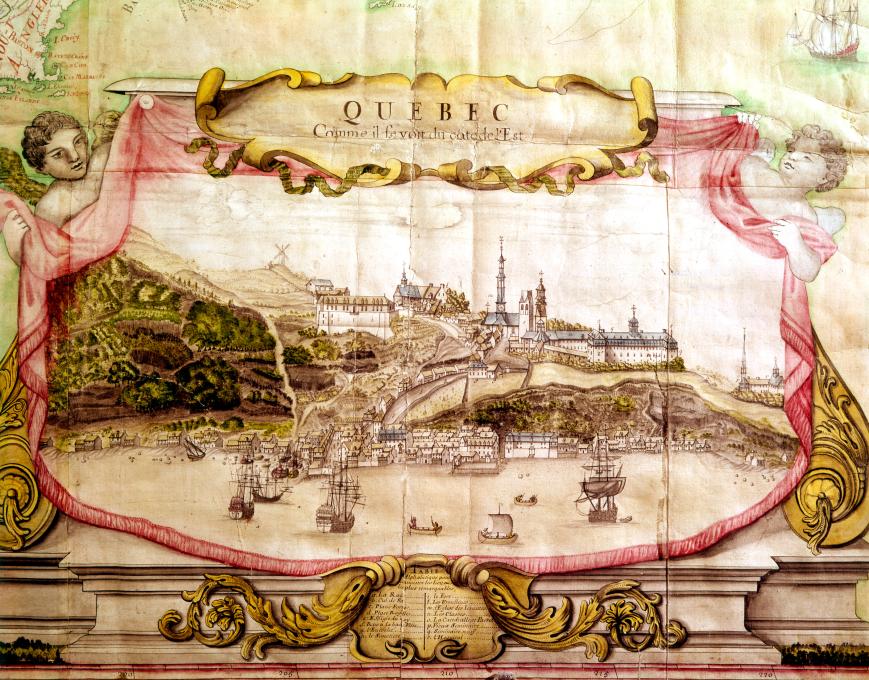

View of Québec in 1688; detail of a map by the King’s Geographer, Jean-Baptiste Franquelin., BAnQ, E6,S7,SS1,P6820179

View of Québec in 1688; detail of a map by the King’s Geographer, Jean-Baptiste Franquelin., BAnQ, E6,S7,SS1,P6820179

An image of Québec made in 1688, only 80 years after it had begun as a small trading post, shows the impressive French capital already dominated by large institutions. The town was divided into two main sectors that are still important today.

The lower town, where the merchants were gathered, was close to the only transportation routes of the time, the St. Lawrence River and the other waterways. The upper town, protected by steep cliffs, was where the governor’s residence, the Chateau St. Louis, was located ─ almost exactly where the famous Château Frontenac stands today.

Religious institutions also dominate the view of the upper town (from left to right): the Ursuline Convent founded in 1639, the Jesuit College founded in 1635, one year before Harvard University, the Notre-Dame de Québec Cathedral and the Seminary of Québec, founded in 1663. One of the most remarkable things about this city is that all these religious institutions, except for the Jesuit College, are still in the same locations where they stood when the image was made in the 1680s.

Struggle for a Continent

By the 1740s, the French, whose policy was to seek commercial and military alliances with Indigenous peoples, had been able to establish outposts across the western prairies, all the way to the foot of the Rocky Mountains.

The English colonies, on the other hand, were still confined to a much smaller area, hemmed in between the Atlantic Ocean and the Appalachian Mountains. With a much larger population than that of the French, the English wanted to expand into the west – but they couldn’t ─ because they were blocked by the French and their Indigenous allies. It was thus inevitable that the French and English would come into conflict with one another, in a struggle to control this continent.

A major attack was launched by the English in 1690, when a fleet of warships sailed from Boston to lay siege to Québec. The attackers were pushed back by Governor Frontenac and the French troops of the city. The English tried again in 1711. This time, an even larger fleet departed from Boston, but never reached the French capital. Caught in a thick fog on the Saint Lawrence, some of the English ships went up on reefs and sank, and over a thousand men drowned. What remained of the diminished fleet turned around and went back to Boston.

A World at War

View of the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Victoires. Richard Short BAC (C-000357)

View of the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Victoires. Richard Short BAC (C-000357)

Rivalry for the lands to the west of the Appalachian Mountains led to increasing confrontations, culminating in what Winston Churchill would later refer to as the first true World War. The fighting began in 1754, with a skirmish near the present site of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. By 1756, “The French and Indian War,” in North America, had evolved into the Seven Years War, spreading to Europe, India, and Africa.

In 1759, the days of New France came to an end for Québec with the arrival of a huge British fleet: over 200 sailing ships, 13,500 sailors, 8,500 soldiers. The British had great difficulty taking Québec, but they had no difficulty in destroying most of the town. From the earliest days of the siege, they set up artillery on the cliffs across the river. From there, they fired thousands of incendiary bombs into the town. Québec was as badly damaged as almost any city in modern warfare.

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham

BANQ. Vue de la Prise de Quebec le 13 septembre 1759/Laurie &Whittle 1797, (P600,S5,PGC49)

BANQ. Vue de la Prise de Quebec le 13 septembre 1759/Laurie &Whittle 1797, (P600,S5,PGC49)

On the 13th of September, in the early hours of the morning, when it was still quite dark, 4500 British troops began to drift down with the tide in small landing craft. They scaled the cliffs and reached an open area, west of the city, known as the Plains of Abraham. After the short battle of the Plains of Abraham, the British were victorious, chasing the French back toward the walls of the town. The British general, James Wolfe, and the French general, the Marquis de Montcalm, were both mortally wounded.

Wolfe died on the field of battle and Montcalm within the walls of the city the following day. Québec surrendered to the British, five days later. The following spring, a large French army returned and soundly defeated the British, in the Battle of Ste-Foy, but failed to retake the city itself. With the surrender of Montreal to the British in September of 1760, the fate of New France was sealed, but the conflict in Europe and around the world as far away as the Philippines continued to rage for another four years until a peace treaty was finally signed in 1763.

The Treaty of Paris in 1763

With the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the French relinquished control of mainland North America, only keeping the fishing islands of St-Pierre and Miquelon off the coast of Newfoundland and their rich sugar islands in the Caribbean.

Québec, the former capital of New France, now became the principal town of a new British colony, called “The Province of Québec.” This colony, which existed from 1763 until 1791, was much smaller than the Canadian province of Québec today. In contrast to the vast territories that had formerly been claimed by France, the boundaries of the new province did not extend far beyond the densely settled areas along the St. Lawrence River and its tributaries, where most of the French population was concentrated.

Westward Expansion Leads to More Conflict

With their French rivals no longer a threat, Anglo-American colonists were now ready to move west. But the influx of settlers soon led to conflict with the native peoples, sparking a major uprising, led by the Odawa chief Pontiac.

After the fighting subsided, the British, wanting to avoid more bloodshed, decided to create a vast “Indian Reserve” extending westward from the Appalachians to the Mississippi and south all the way to Florida. This move by the British was very unpopular among the inhabitants of the thirteen colonies, who were thus confined to the eastern seaboard.

Québec Act of 1774 and the American Revolution

Then, with the Québec Act of 1774, the British Parliament adopted legislation that favoured the French-speaking population of the Province of Québec, but soon led to increasing tensions with the American thirteen colonies. The Act recognized French civil law and the Catholic religion. It also extended the boundaries of the Province of Québec into territories that had been long coveted by the American colonists, reaching southward, all the way down to the Ohio River. American ambitions for westward expansion were frustrated once more. From the American point of view, this was an intolerable act ─ one of many that would spark the American Revolution.

In 1775, two American armies launched an invasion into Canada. They besieged Québec but failed to take the town. After occupying Montreal over the winter, the revolutionaries were obliged to withdraw in the spring of 1776, when British reinforcements arrived.

While their invasion of Canada was not successful, the Americans did, of course, go on to win their War of Independence. This meant that cities such as Boston, New York and Philadelphia could no longer serve as centres of British power. And so, ironically, it was Québec, the former capital of New France, that became the capital of British North America.

One of the Greatest Ports on the Continent

- The timber trade was big business in 19th-century Québec. John Thompson, 1891, BAnQ (C006073)

Québec City began its greatest period of economic expansion in the early 19th century, during the Napoleonic Wars. When France cut Great Britain off from its supply sources for wood in the Baltic region in 1806, the British turned to their colonies and Québec City became one of the most important centres for the export of wood in the British Empire.

Fortunes were made as Britain’s need for wood and wooden ships transformed this little colonial town into one of the foremost ports of North America during the first decades of the 19th century. The shoreline was transformed on both sides of the St. Lawrence and along the St. Charles River, as every cove was filled with wood and shipbuilders launched over 1600 square-rigged sailing vessels.

Economic Decline and Hard Times

Québec City’s expansion, however, was to slow down considerably in the second half of the 19th century. Once more, these changes had their origin with events that took place far from Québec City. Great Britain decided to adopt a policy of free trade and removed protective tariffs that had stimulated the timber trade in Canada. To make matters worse, the British were now making metal ships at home and no longer needed the wooden ships of Québec City.

Business leaders in Canada now turned towards developing the west and building stronger links with the United States. Montreal, more centrally located and surrounded by rich agricultural land to help with its expansion, began to take Québec City’s place as the country’s most important town. With the construction of canals and railways, Montreal became the transportation and financial hub of Canada. To improve their situation further, Montreal business interests had a channel dug in the St. Lawrence so that it became possible for ocean-going ships to bypass Québec City altogether.

A City Preserved: Tradition and Modernity

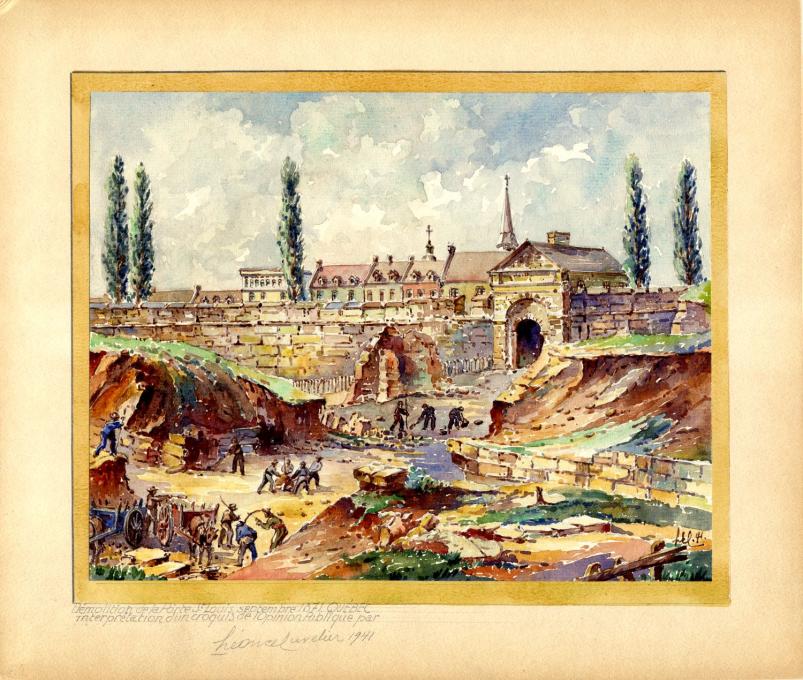

Demolition of the St. Louis Gate, Fonds Léonce-É. Cuvelier, BAnQ

Demolition of the St. Louis Gate, Fonds Léonce-É. Cuvelier, BAnQ

The latter part of the 19th century was a crucial time in the history of Québec City. With hindsight, we can say that the difficult economic period that the town went through probably helped to preserve Québec’s Old City. There wasn’t as much pressure to demolish and build as there was in other more successful North American cities. Equally, if not more important, was the vision of certain key individuals who saw the benefits of preserving Québec City’s rich architectural heritage.

The decline of the city did, however, lead to calls for modernization. No longer in danger of military attack, the City of Québec requested permission from the federal government to demolish the fortifications. Demolition of the outer works, and the city gates, began at the beginning of the 1870’s. Had it not been for the intervention of the Governor General of Canada, Lord Dufferin, Québec City’s fortification walls might have been lost forever.

The Fortifications Are Saved From Destruction

André-Olivier Lyra

André-Olivier Lyra

Lord Dufferin fell in love with the romantic beauty of Québec City and led a campaign to save the walls of the town. His project called for the construction of new gates, wide enough for the traffic to flow though more easily. This compromise showed that it was possible to preserve important elements of the city’s heritage while adapting to the changing transportation needs of a modern city. Today, structures such as the St. Louis Gate and St. John Gate are still wide enough to allow passage of two tour buses at the same time.

The new gates, proposed by Irish architect William Lynn, looked nothing like the narrow military gates of Québec City’s past. They were romantic structures, with towers and turrets, inspired by the defensive architecture of the Middle Ages. The evocative architecture of Lord Dufferin’s project would set the tone for the construction of other picturesque, castle-like structures at the end of the 19th century, helping to redefine the city’s image. Buildings such as the Military Drill Hall and the renowned Château Frontenac came to embody the drama and romance of Québec City’s history for visitors from around the world.

The preservation of the fortifications helped to identify the area within the walls as a special place, where history was considered to be important. Nevertheless, there was still no legal protection for the area. Historic buildings remained threatened and quite a few were demolished. Finally, in 1963, Québec’s Old City, including both the upper and the lower town, was designated as a historic district. There are now laws to protect the unique character of the area and generous grants to help property owners maintain and restore their buildings.

Lord Dufferin’s project, which saved the walls of the city in the 1870’s, served as an example that was to influence Québec City’s evolution for generations to come. Today, as in the past, some of the most successful urban planning and architectural projects in Québec City are based on a creative mix of tradition and modernity. There is now a consensus that Québec City’s high quality of life and economic prosperity are directly tied to the preservation of the city’s human scale and historic character.

A UNESCO World Heritage Site

Jeff Frenette Photography

Jeff Frenette Photography

In 1985, Québec City’s historic district became the first urban ensemble in North America to be declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. The attribution recognized the city’s role as the birthplace of French civilization in North America, and as the only remaining city on this continent (north of Mexico) still surrounded by fortification walls.

French and British Influences in Québec City

Jeff Frenette Photography

Jeff Frenette Photography

In many ways it is the combination of British and French influences in the architecture here that makes the city unique. Exploring Québec City and its region, we find these combined influences everywhere, from official buildings and institutions to commercial and residential architecture.

For example, the typical mid-19th century house in Old Québec is based on the tall, narrow, London row house in its general dimensions and interior plan but retains certain practical features of local French traditional architecture: steep roofs so that the snow will slide off easily and fire walls rising above the roof line to help stop the spread of flames.

This mixture of French and British influences permeates almost every aspect of our environment in Québec City and is so familiar that it generally passes unnoticed by most of the population. Very often, however, when French-speaking Québeckers go to Europe for the first time, they are surprised to discover that ─ in some ways at least ─ they feel more at home in London than in Paris. The language is different, but the urban environment, the houses, the institutions, and the way of life are all strangely familiar. On the other hand, in Paris, the language is the same, but some aspects of the way of life feel quite foreign.

Québec Main Historic Sites Are Just a Few Minutes’ Walk Away

Exploring Québec City’s historic district feels like going to Europe, without having to cross the Atlantic. Must-see architecture in Québec City includes the courtyard of the Seminary, where we can still get a sense of how the city would have looked in the 18th century. Surrounded by its stark, whitewashed stone buildings and steep roofs, one feels suddenly transported to France.

There is so much discover in Québec City and most of the historic sites are concentrated in the area within the fortification walls, just a few minutes’ walk from each other. There is a wealth of history to discover around every corner and many churches and religious sites to visit.

We strongly recommend taking a Québec City tour upon arrival to fully enjoy the rich heritage of the city during your stay.

You can also plan your stay to visit these 15 historic places that bring Québec City's key moments to life.